How to Say Goodbye in China

How to Say Goodbye in ChinaPart Four

How to Get an Apartment in China

My friend Wang Dawei, the geologist, had brought me a publicity release to proofread that Foreign Affairs (of which he is associate director) was putting out in English.

"You come see us sometime. Anytime. You come," he urged. In America, of course, such phrases don't mean anything. In China, that's an invitation.

The total Geselligkeit of the Chinese extended family spills over onto non-relatives, friends and acquaintances, who are expected and welcome to wander in occasionally, unannounced and unappointed.

"Oh, my place, very small, very crowded, I know." This was not the ordinarily obligatory self-effacement of host to guest, but simple fact. His immediate family of four lives in the usual three small, bare concrete rooms on the fourth floor of the usual massive, filthy, stench- and racket-ridden apartment building. The closet-sized kitchen has a concrete basin with cold running (usually) water, undrinkably septic. There is no other plumbing in the apartment; one washroom with a squathole toilet, all drear wet dark smelly concrete, serves each floor. A little stove burns one honeycomb coke brick to keep the teapot gurgling, but wouldn't make much heat even if its flue didn't have to be stuck out an open window. You cook in the wok on the propane burner. A small fridge, a color TV, the imperative new ghettoblasting boombox, and half a dozen bare ceiling-hung light bulbs give the shockingly casual electric wiring plenty to do. Furniture barely leaves stumbling space, storage climbs the walls.

It ought to be grim, but, like Wang himself, it's full of bounce and humor and good cooking and toughness and children and love, and that's why they can leave the windows open all winter and it's warm anyway.

But at the moment we're hosting him in our quarters for foreign devils. After untwisting a few awkwardities in his press release, I pointed to the two new six-floor apartment towers recently added to the view from our balcony.

"Well, maybe you can move in there," I suggested. "They've been sitting empty for a couple months now. The apartments are pretty nice." Three bedrooms, living room, kitchen, private toilet and shower, some tile and paint.

"Oh. No. That building is 80 points. I have 73."

"Points?"

"Points. Housing points. To get new apartment."

"How does that work?" I led.

"Okay, how to calculate. I came here in 1955. Fifty-five to '87, 32 years, 32 points."

"One point a year for continuous service in a work unit?"

"Right. Then Associate Professor, 35points. Full Professor or Vice-President, they get 40, lecturer or something, they get less."

"Okay, that's 67."

"Then if your wife is higher than lecturer, 1 point" (she is a surgeon in the university hospital). "Nurse, get 3 points. Nobody wants to be, very bad job. Or cook. 3 points. Get up in the middle of the night, work hard all day. Nobody wants it, so they give more points."

"Wife is a doctor, 1 point. You're up to 68."

"Four people in family, 4 points. Now how much?

"72."

"Oh yeah. Children of different sex. 1 point."

"I see, so maybe you could get separate rooms for them. But 1 point, that doesn't help much, does it?"

"No."

"So you have 73. How else can you get points?"

"Well, one or two points if your parents are Overseas Chinese" (that means any refugee from liberation, mainly residents of Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao, officially called "compatriots," but also can include just about anybody of Chinese male ancestry not politically anathematized).

"What's that got to do with it?"

"They live abroad, they get used to lots of room and luxury, they expect it when they come to visit."

"You mean you get the extra points even if they don't live with you?"

"Right. For parents. Couple points, maybe."

The idea behind this, proselyting expatriates to the fatherland's cause, is either glorious or maniacal, depending on how you want to read the record of ethnic recruiting in history. Reincorporation of Hong Kong and Macao, as somehow naturally Chinese, has been agreed to, and of Taiwan looks inevitable. The argument gets spread pretty thin when streched continentally where seldom used to be heard a Chinese word, over Mongolia, up the Silk Road all the way into Kazakhstan, down across the whole Taklimakan Desert and back up over the Tibetan Plateau to the Himalayas. Where it spills past them it starts bloody fights. How will it be greeted in Singapore and Maylasia, or, say, on San Francisco's Grant Avenue, or in Chinatown Houston?

"This place," Wang waved his hand around our quarters, "at least 100 points. Would have to be governor of province, or minister."

"Or white literature scholar, used to living at the bottom," I teased him.

We have a two-room suite connected by a hall and private bath, with tub (rarely hot water) and flush pot, some 40m2 for the two of us. The average per capita city floor space is about 6m2. We have marble-chip floors (brutally cold), painted stucco walls, no broken panes in the screened, steel-frame casement windows (which leak badly anyway), tile bathroom, and share a sitting room and kitchen-sized but primitive kitchen with 3 other floor suites. TV cable (up to 4 evening channels), no exposed wiring. The ponderous radiators of the central heating system (I think no other campus building has one) stand cold and grim; the boiler doesn't work. On the collected list of explanations why not, I assign top credibility to its being Russian-built. It is now politically too cold to get parts for it.

Wang pointed to the Japanese-made heat pump over our balcony door.

"Maybe not even ministers have air conditioning. Very special. "

"Oh? But they have them right there in the cadre house."

Next to the guest center where we live is a kind of clubhouse for senior, retired functionaries, who gather to smoke, drink tea, read the People's Daily, noisily contend at cards or xiangqi (Chinese chess) or just talk (which sounds to a Westerner like one hell of an argument).

"Right. Very special. Members of the Party before 1949. You have to be careful, be nice to them. They have friends, know people very high up. They don't like something, you have trouble."

"So they get air conditioning and the governor doesn't?"

"Well, they only run it in the afternoon. But if you have a relative who is high cadre, an uncle maybe, you can get some more housing points."

It was starting to sound familiar.

"Dawei," I said, "I've heard so much about guanxi--connections--that's the way we do things too, in our capitalist system that's supposed to be so corrupt. What's the big difference?"

He laughed the way Chinese do when they need to keep something discomfiting under control.

A week later I met him on the street (walking down a campus street with Wang is about like trying to wade through a very friendly cocktail party).

"About that point system," I started. "What if your wife is a professor too? Does she get all her points?"

"Nono, just one in the family, so you take whoever has the highest score. She would get 35, like me, so no difference."

"The place where you live now--how many points to get in there?"

"That's an old building, before points. Points just for new places, since maybe last five or six years" (much greeting and bantering with nearly everybody on the street).

"I figure you get your wife classified as a nurse, teach your son to cook, and next year you can move into the new place."

"Oh, pretty soon they build another one, we can have it, by then it's old. Things in China are so bad, housing very bad, not enough" (waving, shaking hands, trading chummy insults).

"Bad? The population has doubled in 30 years, another half billion people, but now you all have a place to live, instead of in the gutters. The kids are mostly going to school, nobody has to starve, and apartments built a couple years ago are already old, the new ones are so much better and going up so fast. What this country has done is almost unbelievable. Look at what it was like ten years ago, and look at it now. How will it be in another ten years?"

He laughed, the way Chinese do when they need to keep something discomfiting under control.

We have been guests in the homes of many other faculty and staff. What surprises me, a practicing cynic, is not the string-pulling, universal as it is, but how little difference rank and influence can really make. It is astonishing how evenly the misery is spread. By his living quarters, you couldn't tell a groundskeeper from a department head. The president of the university, Wang Dianzuo, Professor of Geology and jolly banquet partner, wears jogging shoes and workman's blues, stands in line with the rest of us for popsicles or postage stamps, shovels up rice with dirty chopsticks in the dining hall, jokes with Wang Dawei and his buddies on the street, and lives in a concrete apartment house. I don't know whether he dreams of someday having a Toyota and a garden and a credit card. Those are not the sort of things the spectrum of Chinese ambition splits up into. The one most nearly universal longing I have heard is to someday travel, study, or work abroad, to see and taste and cautiously test that bizarre universe of wealth and license, to try both it and oneself, like an acolyte touring Sodom. But please remember that almost everyone I know and talk to is some kind of mind person, for every one of whom there must be ten thousand without the dimmest suspicion that any such antimatter cosmos as the ambitious intellect exists.

I have heard rumors that a high percentage of the few who do get out don't come back. Obviously, there is no way to confirm this (Umm. See Epilogue). But also obviously, if so, the Beijing powers either see in it no great threat or may even welcome it as a convenient dissident drain, else there would be the typically incongruous yoking of vigorous denials that it happens at all with fulminations about the evil foreign seductiocoercions causing it.

Two opposed constellations of forces work on any Chinese thinking about trying to get out. The image of Western affluence and liberty beckons; cultural identity restrains. Right at the balance point of these pulls is the idea of freedom. To be Chinese is both to yearn for freedom and fear it. Socialism's endless structure and control are not the intolerable oppressions to a Chinese they would be to an American, but rather, I think, in themselves an expression of deeply rooted habits of Chinese thought.

The Chinese Communists, however frightful or ridiculous they may look,or murderous they may have been, can claim to have racked up an astounding record of net social progress by dovetailing their programs and methods with those thought habits. Where does the credit for such accomplishments really belong? To us leisure- and freedom-loving capitalists, the flaw in Marxo-Maoism is its stunning boredom, the guarantee that any state so founded, paradoxically, would be sure to wither away, an insignificant, appendicile rigamarole that couldn't make the half-time show. And the terror with which the Party reacts to the slightest taint of liberalism underscores how easily the entire Marxist-Leninist fabric will disintegrate if the benefits it strives to confer do bring widespread pleasure. Nobody is going to attend a Party congress who could go on a picnic instead. Communism has been the powerful unifying instrument, not the cause, of the miracle that has brought China from chaos and slavery to the edge of modern greatness. The nuclear energy has come from the boundless and ageless optimism, endurance, and practicality of this people. No form of government can claim to have created those qualities, and any that tries to stand in their way will fall.

How to Say Goodbye in China

How to Say Goodbye in China

In China the seasons change, like everything else, officially. One day everybody is waddling around in quilted layers of blue, the steaming heat notwithstanding; the next they blossom into filmy nothings in defiance of late Mongolian northers.

Winter dress in Changsha, a provincial capital, is stalwart. Hair-rigging, bangles, or facepaint are rare, even on the teenagers. It can be a shock when the occasional dowdy marketwoman wears perfume. Who expects people haggling over the most appalling plattersful of guts to smell like flowers? Transistor-borne disco plague has started a few local style infections, but nothing epidemic yet. Heel heights, always a sensitive indicator, have just started up, for both genders. When a girl skipped through the market the other day in silver three-inchers, for once not everybody was staring at me. I did not see a skirt or dress as streetwear before May Day. Women's outfits can be had in brocades and embroideries and bright solids and prints--one zebra coat looked like a lighthouse in the dark blue sea--and nice furs are popular, but nothing shows any shape. The extreme in guy style (boys, not men) has got about as far as early dancehall gigolo. Men all look like Mao.

Summer Chinese look like a different species. Men go for plastic sandals, shorts, and an undershirt, suitable attire for almost everywhere, but carry along a shirt to drape over, unbuttoned, if formality requires. Women turn out in skirts. The girls like gauzy seethrough blouses over a ridiculous little bra, anatomically superfluous (Chinese women just don't grow big milk glands). Grannies look about the same, only looser.

Nobody seemed to know when the semester was supposed to end. I had figured out that the good people in the language department didn't feel comfortable about giving me orders. They much preferred to have their honored foreign expert make the decisions. It was a nice feeling, after all those years of rule by schedule and catalog. I had already proclaimed the abolition of exams in my classes (this will at last happen everywhere when my teachings are embraced, and higher education will live again.) I oracled around with the airline schedules and announced our departure date.

You want to be careful about giving

presents in China. They retaliate. A harmless trinket can

entrammel you in a potlatch war. As it was, we were hit with a

couple of unprovoked banquets, silks, embroideries, fans, cute

little Chinese boxes, a bamboo wall scroll with furry pandas,

engraved chopsticks, porcelain artwork plates, boxed and

dedicated vase sets, teapots, books, all delivered with

declarations of pan-Pacific solidarity and much good will.

For Julia's 18th birthday, the expatriate

Anglo community threw a party in the middle of the street in

front of the Sichuan Restaurant, with cake properly on fire,

goofy presents, singing and hollering, plenty food and beer, and

a speech (by Julia). We were making such an uproar and blocking

traffic so thoroughly that for once nobody paid much attention to

us, so normally were we behaving. We finally belonged.

Foreign Affairs sent off a delegate to

Beijing with our passports to work on plane tickets. We would

meet him there a few days before departure and do the town. They

also got us sleeper berths for the 23-hour train ride there. If

you really have to get somewhere in China, suffer the train. It

will go. Domestic air travel is more for folks who just enjoy

sleeping in airports.

We packed up our awesome burdens of

mementos and filthy clothes and pictures and pencils and old

tennis shoes and all the inexcusable trash people haul around the

world with them. A couple hours before our late evening

departure, another party started brewing. Pretty soon we were

going strong in about seven languages. They all came. I love

them. You hear, you guys? I love you.

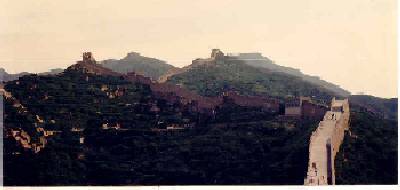

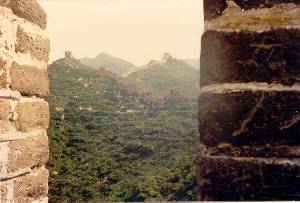

The trouble with Beijing is its scale. The

human confronted with centuries and palaces in such dimension

finds it hard to see life as anything but a desperate

undertaking. And here you're always in the presence of that most

monumental attempt to make sense of it, the Great Wall. It was

started two millenia ago with the same obsession for keeping out

the rest of the world that still governs Chinese thinking today.

At least China has never suffered from the grand delusion that

other peoples are inferior, destined merely to be fodder for the

master race; we and our brethren are barbarians, of course,

incorrigibly corrupt, but dangerous and powerful. We are made the

cause of every ill from high treason to fleas. Smugglers,

rapists, demonstration instigators, pornerasts, noisy advocates

of press freedom or private ownership, the huaifenzi, bad

elements opposed to orthodox policy, invariably turn out to be

foreigners or suffering a direct infection of exotic virus.

The wall embodies the central Chinese idea,

and we do well to contemplate it. Let's play with this idea a

little bit. The wall was built and rebuilt over the centuries by

China's most ambitious and successful warlords. These

architectural eons cannot now be mentioned without a pious

shudder at the hideous oppressions thus wrought upon the people,

the working class that communism apotheosizes as unappeasably as

ever an emperor enslaved them. The point is that the

warlord-emperor-son of heaven was doing the only thing he could

do to identify his conquered millions, to isolate and protect

them from others exactly like himself, and was therefore suitably

deified. The wall came to mean what it is to be Chinese. When a

dynasty at last rotted, a new lord climbed in and had another

mountainful of stones faced onto the old earthwork backbone, the

immense, crumbling ruin still snaking for mile after mile over

ridgecrests and deserts. The refaçaded and tourist-entrapped

sections now on exhibit were repaired by exactly the same

barehanded labor methods always used and for exactly the same

reasons.

Mutatis mutandis, of course. In the

world as it is now, walls, whether ideal or stone, don't work the

way they once did. When Thebes and Teotihuacan rose, a civilization

was a palace for the gods in the wilderness. But now that the

wilderness has just about filled up, it's no longer so simple to

tell the inside from the outside.

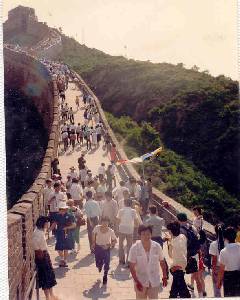

At Badaling, the road from Beijing to

Mongolia chokes through a massive gate in the wall. Traffic in

the tunnel between the parking lots and tourist clutter on both

sides is by one lane, with a stoplight and ineffectual cops

trying to make it take turns. The jam of buses and cars and

trucks and motorcycles and hikers stretches down the mountainside

for miles in both directions. In this swarm the white man

outnumbers the yellow. He comes now very much by invitation,

troops along behind or tries to get away from his guide, who

dispenses doctrinally correct history and statistics, advises on

best views and exposure values, then steers his charges into the

stores hopefully aburst with gorgeous carpetry and godawful

gewgaws, all for special selection by honored foreign guest

please, sure we take your American Express card. Welcome to

China. This is it.

The same strange, trapezoidal restretching

of history over doctrines confuses the visitor to the Palace

Museum, as the old Forbidden City is now called, being forbidden

only if you don't have 5 Yuan FEC. I could not extract any one

clear Chinese attitude toward these stupefying expanses of courts

and halls and gardens. There is something forlorn about the great

state portrait of Mao still pinned up over the front gate (a story going around says it gets a little smaller each year). The

monumentality he tried so hard to assume is swallowing him, as it

did all the others who looked down on it from above. Because it

was not born and does not come from above. Once the conqueror

sets foot on the first step to ascension, he is on his way out.

The People don't live in heaven. They never will. They don't want

to. They take some kind of satisfaction in the incalculable labor

of building it, but when it comes to finding somebody to live

there, they have always had a lot of trouble. Across the doorways

to the infinitely detailed Hall of Supreme Harmony are barred

iron gates, through which the hordes of paying spectators strain

to make out some coherent vision of the gloomily golden profusion

within. No one sits on the coronation throne, almost invisible in

the center darkness.

Go to Epilogue