In the city of Verdun, well-known throughout the kingdom of France, there lived two merchants, between whom the bond of friendship had come to be such that either would think nothing of risking his honor, possessions, and life for the other. Yet as God had willed, one of them, named Gilbert, was so rich that his friend William, a poor man, might have served him as does a serf his lord.

Now, it came about that Gilbert took on the responsibility of governing the city. He searched for some way in which he might establish William's reputation and estate, with the idea that their friendship would then be such an example of harmony and stability for the whole city that no disunity could prevail against the two of them. Having given this matter long consideration in his own mind, he at last brought himself to mention it to his wife. One night as they lay abed, he told her what he had decided to do.

"My dear wife, I intend to give our daughter Irma in marriage to Bertram, my friend William's son. We may thus be all one happy family, and govern the city in peace."

"Husband, what are you saying?" she replied. "Have you lost your senses?"

"Now, hold your tongue until you understand me a little better. I know very well what it is that troubles you about this. There are plenty of counts and dukes who would be only too glad to have our daughter, if I were to take it into my head to give her to one of them. But I will not have it. A nobleman would soon treat her as just another one of his cattle, since she would not be his equal, and that would break my heart. No, my daughter shall have a man of her own station in life."

"Well, do just as you will," sighed his wife.

"Bless you," said Gilbert. "You have always been obedient to me in all things, and I will love you for that and your many other virtues to the end of my days. Now, we'll waste no more time, but settle this affair right away."

At first light, Gilbert sought out William and inquired after Bertram. "Where is he? He has but to consent, and he shall have my daughter to wife. As God is my witness, there is no one I would rather have as son-in-law."

"Oh, no," exclaimed William. "Why do you so make sport with me? I have long been like a servant to you, and am content that you should only permit me still to be so. That is reward enough for me."

"Indeed, this is no idle banter," Gilbert assured him. "What would I be thinking of, to make jests at your expense? No, it shall be so. Send for your son!"

And so it came about that Bertram and Irma were brought together, and she was betrothed to him in lawful wedlock. The story has it that the lovely girl wept at his embrace, as well befitted her modesty and innocence, and to be sure, I would take offense to hear of a maid who remained unaffrighted upon being given to a man she had scarcely seen before. But the marriage was as splendid as could be, and when the setting sun yielded its place to the evening star, the two of them went to share one bed, where over some thousand of kisses they soon came to terms.

When the day dawned on their gladness, Bertram took his lady by the hand and led her to the hall where the musicians were already raising a joyous racket with drums, fiddles, and pipes. The women were arrayed in their finery, the tables were decked with fresh linens and delicacies, and the floor was strewn with blossoms. When the guests had washed their hands, the stewards and cellarers wasted no time in serving them abundantly. The best give their best, and it was not Gilbert's intent to spare his goods on this occasion.

After all the celebrations, young Bertram took his bride home with him. He loved her dearly, and so did she him, such that never before or perhaps even after was such a loving and harmonious couple to be found anywhere. They never quarreled. Her wish was also his, and what pleased him was what she wanted. In short, God had granted them a paradise here on earth. There never lived a poet so wise as to be able to tell truly of the indissoluble love that united them.

I should tell you also that over the following years young Bertram, with the thrifty aid of his wife Irma, managed his household with care, adding considerably to his possessions through his skill as a merchant. He was knowledgeable about all sorts of goods and clever at trading them. His great opportunity came with the approach of the market fair at Provins, for which he began to prepare. He gathered fine cottons, silks, and scarlets, and such other kinds of cloths as bring the best profits. Then he went to take leave of his wife.

When she heard that he was going away, her heart felt a heavy burden, for she was afraid he would not be back soon. She wept hotly. He took her in his arms and kissed her over and over, but she said: "my dearest husband, in whose care do you leave me? Sorrows bear down on me because you are going away, and I will have no joy until you return."

"Lovely wife," he replied, his own eyes reddening, "why do you trouble me by tormenting yourself? God will watch over you for me. You know that I will always be devoted to you; I will be back shortly, God willing, and until I return, I carry your sorrow in my own heart."

Then Bertram departed for the city of Provins, taking with him what must have been a good ten thousand marks worth of stuffs. On arriving, he asked to be shown to the very best inn the city had to offer. He received an elegant welcome there from the innkeeper, who provided him with lodgings where the goods he had brought could be kept secure from any fear of loss.

When arrangements for the new guest had been completed, he was invited to the wide dining hall, where the table was surrounded by many rich merchants from far and near. The innkeeper asked his guests to stay on after dinner for a round of conviviality. He suggested that each tell something about his own wife.

"That's a good idea," said one, "and I'll tell you, mine is a miserable thing. She's a devil, not a woman! Why, not even one of the fiends of hell would dare set foot in my house."

"Well, we hear what you say," rejoined another, "but I think you wrong your good lady. Mine is not like that. She's kind and generous--in fact, as soon as I'm out of the house, she starts showing such love for her fellow man that now I'm raising two bastards."

"That's loving of her indeed," continued a third. "My wife's great virtue is constancy. Yes, she drinks with such constancy that she's just about accounted for my house and everything I own."

As the story went round the table, each of the merchants took his turn to slander his own wife and thus also his own reputation. Young Bertram listened quietly, thanking God all the while for having so favored him with a good wife.

"How now, sir," said Hugh, the innkeeper, addressing Bertram. "Won't you add to the cheer and give us a story about your woman?"

"So be it," said the youth. "I have at home a pure wife whose love has made me very happy. My heart laughs when my eyes look on her. And she loves me as no woman ever did any man. She's chaste, modest, and ladylike, and along with her good sense, she knows how to behave properly. I can say no more in her praise than that she is the full blossom of womanhood and my heart's delight."

"Oh, come, now," snorted Hugh, "you're crazy if you believe all that."

"It is the truth," Bertram declared. "I can scarcely describe half her goodness to you."

"You really shouldn't stretch things so," remarked Hugh. "You don't make yourself look any better by prattling things about your wife that no one is going to believe. Why, I'll wager you that I can bring her to bed within six months, if you'll give me a free hand to try. How about it? All or nothing--everything I have against all you own. We can swear an oath on it right now, so the loser won't be able to back out."

Bertram agreed, and they avowed the terms then and there. They sent to tell Irma that Bertram had gone on to Venice, and that she would have to take care of things until her loving master returned. Her heart swelled with anguish at this word, and tears rained down her cheeks, but she commended her dear husband to God, composed herself, and set about caring for her household.

Meanwhile, Hugh, the proud and crafty innkeeper, had come to Verdun and taken lodgings close by, so that whenever Irma set foot outside her door, he was there with a bow and a greeting that she could not avoid returning. Soon he was in high spirits at the prospect of his success. "I'm going to work this so that I get the goods and the woman both," he gloated. He spent day and night scheming as to how he might gain his end, meanwhile showering her with all sorts of gifts and attention. But Irma trampled his presents under her heel in disgust and sent him a warning that she would complain about him to her friends, from whom he could expect to receive a beating.

Seeing the failure of his direct approach, Hugh determined to promote himself among the household servants. He gave them expensive presents and promised them more, if they would take every chance to speak well of him to their mistress. But when they did, she silenced them. "You'll have to find another buyer for the dirty wares you're hawking--I'll have none of them. Now stop your prating, or I'll have you all thrashed!" They quickly began to talk of other things, and didn't mention Hugh again.

Hugh was beginning to worry, since the time remaining was getting short, and he was making no progress at all. He found a new stratagem. One morning at church, he accosted Irma's handmaid Emily. "No man ever suffered as I do," he lamented to her. "I must have your mistress, or I die! Would you like to earn a good reward?"

"Indeed I would," said Emily.

He tucked a gold piece into her bodice on the spot and promised her much more. "Go to your mistress and tell her she may have whatever she asks--I'll pay a hundred marks to have her."

Emily, eager for her reward, wished him good fortune and ran to tell Irma of the offer, but she rebuked her maid sharply. "Shut your mouth and keep it shut about that business," she snapped, "or you'll hurt for it. I have plenty of money--I'm not about to sell my reputation."

Hugh was getting desperate. As the wager deadline drew nearer, he raised the price higher and higher, at last offering a thousand marks for the privilege of spending a single night with mistress Irma.

That was too much for Emily. "My mistress," she began, "what are you thinking of? You do your husband poor service indeed, if you don't take the money. Why, he could labor through a dozen far lands and never earn so much! Please, consider his interests, and don't bring his displeasure upon you."

"Stop your talk," ordered the faithful Irma, "or I'll have you whipped with the rest of them!"

But Emily persisted. "I don't care beans about your threats," she burst out. "You and your honor--we'll see how your husband honors you when he comes home and you tell him you've tossed away a fortune! And you don't have to make a public scandal of it, you know. Just do it quietly, and nobody will find out."

"God forbid that I should ever be a disgrace," said Irma. "Nothing could be worse. And it's a mortal sin, for which I'd deserve to choke in the fumes of hell! Oh, my dear Bertram, if you only knew what I suffer, you would hasten back home!"

Her problem had become such that she now felt the need of advice, so she went to one of her aunts. "Do you think I should tell my father about this?" she asked.

"Tell your father? Whatever for?" said the aunt. "No, just go ahead and do it. I don't think any of your friends, or even I, will think highly of you if you pass up a chance like this. Why, at such a price, the queen would consider it an honor! When he's through, just put your skirt back down, and you'll be the same as ever."

Deeply troubled by this talk, Irma did go to her father and mother. She told them the entire matter, asking them to help her bear up. "Bear up?" snorted Gilbert. "Alas, Bertram, my poor son-in-law! That I should have a daughter without sense enough to catch a fortune before it flies away! Listen, girl. Stop asking silly questions and do what's wanted of you. Are you trying to ruin me? If you let all that money get away, I'll poke your eyes out!"

Irma thought of her chastity and wept. She went also to William and his wife, her parents-in-law, and poured out her woe to them. "Do it, daughter," William advised. "I'll be of whatever help I can. If you don't your back will take a beating when Bertram gets home."

In despair, Irma at last determined to hear what her friends would say about this matter. She sent for them all, and all of them, man and woman, agreed entirely with the advice she had already been given. They left her sitting in tears, turning over in her mind how she might avoid sin, escape scandal, and remain faithful to her beloved husband. "Dear God, have mercy," she prayed, over and over. "Maria, spotless maid, hear my lament, and see my great distress!"

God does not forsake those whose faith in him never wavers. He inspired her with an idea.

"Emily," she called her maid. "You wanted me to take the money all along, and finally even came out and said so. Now tell me--will you, for a hundred marks, lie one night with this fellow?"

Emily did not have to think twice about it. "I'd do it for half that," she assured her mistress.

Irma sighed with relief, and sent to tell Hugh that if he would deliver the full payment, she would do as he wished. He was to tell no one, but come secretly at nightfall. Emily would admit him.

Hugh was overjoyed. He immediately sent the promised thousand marks, and then arrived at the gate with the first sign of dusk. Now, Irma had dressed in her maid's garments, and given her own best robe to Emily, who waited eagerly in her mistress' bedchamber. Irma waited until it was quite dark, and then went to admit Hugh, who, taking her for the maid, supposed that everything was going exactly according to his plans. She welcomed him courteously, and asked him please not to make any noise, to which he readily agreed, tipping her at the same time a good ten marks.

"Oh, thank you, sir. God bless you," whispered Irma. "There's no need to keep you waiting. Come with me, and I'll show you to my lady's bedroom." Again she asked him to go very quietly, which of course he did.

The bedroom was pitch dark. He groped his way to the bed, where Emily gave him a warm reception. She wore a silk shift and an ermine cloak, soft armor indeed, but her other weaponry was such that she had no trouble winning the engagement. He tore off the cloak, and soon the shift also, but she struck back with a kiss that nearly won her the victory then and there. This aroused the fight in him, for he was an old campaigner. He dropped his buckler and rushed her bravely, hurling kisses, but for every one of his that found its mark, he was hit by two in return. It was a long battle, but in the end she won. He had to take such terms as I myself wouldn't mind, since they cost no broken heads or bones.

Thus did Hugh pass the night with Emily until dawn broke, but he never really was out of the dark. Irma, having risen with the morning star, hurried to the chamber door and knocked. "Wake up, sir," she called softly. "You'd better hurry--it will soon be light."

"Yes, I'm coming, Emily," he replied. And then he addressed his bedpartner. "My lady, you must give me a souvenir, so that I'll remember you for the rest of my life."

Emily did not know what to say, and before she could think of something, Hugh took a sharp knife from the pocket of his trousers and cut off one of her fingers. Then he left, paying no attention to her screams. He hurried back to his own city, and as soon as he reached his inn, he went and found Bertram. "Aha!" he announced. "Everything you have is mine."

"I don't believe it!" said Bertram.

"You can't get out of it now," replied Hugh, "I'm taking over everything you have, both here and at home."

Bertram was very frightened and downcast. "How did this fellow do it?" he pondered. "Surely he's lying, just to get whatever he can. I know my wife is faithful. No, she didn't betray me!" And to Hugh he said: "no, I will concede nothing until we have submitted the whole matter to referees."

"That's fine with me," retorted Hugh. "We'll go back to Verdun. There you can call everyone together, for my festival, and all your friends can see for themselves who has won."

When Irma was told that Bertram had returned, she ran to welcome him. "Ah, my dear husband, my heart sings with joy at your arrival," she cried, embracing him. He tried to thank her, but a sigh choked his words, much to her alarm. He set about inviting all his friends to a great feast, thinking that would be best in any case. "I'll certainly be generous with my bread," he said to himself, "since if what Hugh claims is true, it's no longer mine. But if luck is with me, and I win all his possessions, how much more gladly I'll share with my friends!"

While all was being made ready for the feast, sorrow gnawed at Bertram's heart. This was not lost on his wife, who came to him and said: "my dear master, as you love me, tell me what is troubling you, for I will stand by you always."

"Ah, my lady," he sighed, "my heart is plagued with sorrow. Why, I cannot tell you, without insulting your wifely modesty."

"But remember how I have always been obedient to you," she coaxed. "I have always done as you willed. Now you can at least grant me a wish, and tell me your troubles. Who knows? Perhaps I can tell you something that will turn all your sorrow to joy, and make everything come out all right."

At that, he softened, and related to her the whole story of his wager with Hugh.

"Ah," she cried, "forget your misery. For all his tricks, he's ours now, lock, stock, and barrel!"

Greatly relieved, Bertram enjoyed himself no end at the feast. When all the guests had eaten their fill and the tables had been cleared away, Hugh invited the company to stay awhile. He told them why they had been invited to come. They all turned pale as death, but Hugh only laughed.

"Yes, all this is mine," he shouted, and taking the finger from his pocket, he held it up for all to see. "Here's my proof! I cut it off the slut myself, that night, in my house, my bedroom, my bed!"

Every eye turned to Irma. "I can only regret my depravity," she said. "But remember, you were the ones, all of you, who advised me to do it." And then with a peal of laughter, she held up both her hands, with all the fingers spread wide.

As Hugh sputtered with rage, Emily ran into the hall and, showing her mutilated hand, lodged her complaint against him.

"Sir Hugh," said Bertram mildly, "pay me."

"Oh, take it," groaned Hugh. "Take it all, and let me be your poor vassal." Bertram did just that, but at least gave him Emily to wife, along with the hundred marks she had earned, so he could marry her in some style.

This story, which I, Ruprecht of Würzburg, have told, should teach all women, both wives and maids, to tame their lust if they care about their good name. May God and the blessed maid Maria preserve us from the sins of this world and the bonds of hell!

THE TWO MERCHANTS

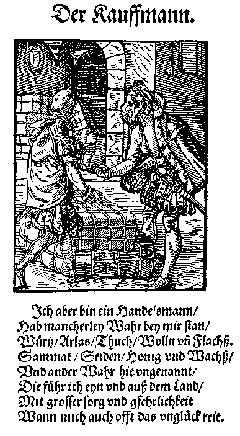

From Eygentliche Beschreibung aller Stände, Frankfurt, 1568.

A merchant and a trader I;

all kinds of wares I sell and buy.

Spices, fabrics, wool and flax,

velvet, honey, silk, and wax

from lands afar my commerce brings,

and countless other useful things.

`Tis trouble sore, for oft as not,

misfortune is the merchant's lot.

Thickwitted and garrulous thought I am, and unaccustomed to composing, I am going to tell you a story. Your indulgence, pray, and may God inspire me!