Part of our vacation project had been to find some use for the wad of currency accumulating from my salary. The Foreign Affairs Office, after much hawing, had finally confirmed that not a farthing of it could be taken out of the country, a disastrous little detail of the vast store of ignorance I had brought along. I had often been reminded I was making many times what a native professor was paid, being of course an honored etcetera accustomed to etcetera standards (translation: spoiled victim of capitalist bosses). There was, of course, another hitch, very Chinese: the extravagances I was expected to crave can't legally be bought in China with Chinese currency, in which I was paid. So, again very Chinese, they put a patch on the hitch. I had a document, called a white card, with photo and embossed seals and signatures and clauses requiring by these presents merchants and sundry purveyors to ignore my racial handicap and accept their own money from me. Said negotiants, being Chinese, of course, attached a catch to the patch, solemnly laying out for my inspection equally officialized papers requiring them to surcharge me 30% if I insisted on trying to pay with People's Money. Remarkable. The standard streetcorner bid, drastically illegal, of course, for foreign exchange certificates is 30% over face value.

Scene: Guangzhou airport. Cast: taxi driver, two aliens.

Driver: Haha, you come! I you ha we take go!

Alien: Dong Fang Hotel.

Driver: (roars off without starting meter)

Alien: Whoa. Start meter.

Driver: After hours. Standard price.

Alien: Stop. No.

Driver: (stops) Late. I take you. Standard price. Ten Yuan. Haha.

Alien: (knows meter price would be seven) Oh, hell, all right.

At hotel. Alien hands driver Chinese 10-Yuan note.

Driver: No, no. FEC (=foreign exchange certificates. Points to sign on dashboard next to dead meter)

Alien: (in his best Mandarin, a foreign language in Guangzhou) Don't have any. Have white card (presents it).

Driver: Aagh! (Cantonese for "Aagh!") White card! (digs out 30% markup papers)

Alien: No. After hours. Standard price. (aliens bail out of taxi)

Driver: Aagh!

Maybe it's absurd to complain about a hotel in China being fake Chinese, and in fact the Dong Fang (roughly "Great Eastern") typifies a very Chinese institution, the chain of huge dollar sinkholes thrown around the borders and planted by every tourist magnet since liberation. These monsters brag of their disco-tennis-sauna-dom and all the haughty obsequiosities the traveler has to pay in hard money to put up with. They're theoretically mandatory for foreigners, off limits to natives, and accept no local currency. The Dong Fang has been accreting for some time around a big courtyard with fishpools, fake rockery, and tiley-curly gazebos draped with plastic vines. Now competition (officially nonexistent, of course, under socialism) from the newer glass skyscrapers has reduced it to honoring white cards. It looked empty to me that night.

Our idea was to blow the last of our Yuan on at least some quasi-luxury. We ate and bathed and watched Hong Kong hoodlum heroes on the tube pretend to kungfu the bejesus (bebuddha?--forget it) out of each other and slept forward to no bugle blasts at dawn. But we still had miles to go, so, presuming to further exploit our expensive VIP-dom, I visited the hotel ticketing service counter first thing in the morning.

"I need two tickets to Changsha, please--"

"No."

"No?"

"You go to CAAC."

"Just a minute. How about the train?"

"No." Both girls began fiddling earnestly with papers on their desks.

"Please. You're the ticketing service, here's the sign. What kind of tickets do you get?"

"Oh. Very crowded. No tickets. You go to train station."

Well, here we don't go again, I muttered. Having once survived the overnight sleeper to Changsha, I decided I'd join battle once more with our old pals at the airline ticket office. After wading around in that standing riot for a couple of hours, I came away with tickets on a flight 3 days hence. We didn't have enough money to stay that long at the hotel. I succeeded in calling Mr. Shen. He had anxiously instructed us to cable him from Hainan Island so he could meet us when we returned and continue hosting us at the research institute. We had of course never known where or when our next arrival would be until the moment it arrived. He was relieved to fetch us back within the walls, to our ministerial suite overlooking and -hearing the hog farm.

At our last banquet before leaving, Shen seemed almost a different person. We had already, before the Hainan trip, begun to break the ice when invited to his apartment for dinner. On the job, shepherding us around, he played the officiously ineffectual functionary, patting his hand and dispensing official absurdities. At home he warmed and loosened. Family was a sturdy-looking wife, at least three grown children, and some personnel of indeterminate relationship, all of whom invariably unshod themselves to cross the new blue carpet in the sitting room, stumbling and giggling back into slippers on the bare concrete hall side. Shen for once took off his western-style jacket, but marched masterfully around on the carpet in his shoes, showing me a small brass Eiffel tower, Italian glass paperweights, a mannikin pis corkscrew with the screw in place of the pis, a little sealed aquarium with a tiny diver who worked when you turned the light on, all mementos of his world travels. We spoke German and ate oranges and cracked watermelon seeds, while in the corner the TV babbled Hongkongese to itself. Girls and women and assorted cousins giggled and lounged with Julia in a bedroom until time to go.

Now, at our goodbye dinner, we reviewed our adventures for him. I said I thought maybe I had been able to buy plane tickets, when he had not, because I was a foreigner. He nodded, and translated for the institute director.

"Here a foreigner can get tickets, and we can't," he said, and the words went on beyond my Chinese, but the tune was about the same.

After the director had toasted us and left, I apologized to Shen for not having been able to let him know when we would get back.

"Things are very bad here, very bad," he said, a cloud over his usually weatherless expression. "Impossible to do anything. Not like Europe. Very different."

I took my cue. "Would you maybe have liked to stay in Vienna?"

Well. He patted the back of his hand. At 60, he said, he didn't want to start a new life. There was his family. They wouldn't have been able to join him, or at least not all of them. The Corporation here, after all, had sent him, and he owed them his services. But most of all, Europe wasn't China. He just--well, belonged here.

As he spoke, I was trying to fine-tune to his main frequency. I had read and heard horror stories about families of travelers abroad being held hostage, in effect, to bolster the potential escapee's national loyalty. I thought about that homey ambience he had let us share in his family. I saw the silent, irresistible smile of his youngest daughter, a slim, winsome deaf mute. And I remembered the pride in his voice whenever he cited some great Chinese accomplishment to us, however improbable or doctrinaire or real. I worried I maybe shouldn't have set shoe on his fine blue carpet. But no, that was the point: to have luxury under foot, at home, in China, for pater familias and honored guest. It wasn't just that his family might never have been allowed to leave. Even if they had been, his way of life and sense of belonging could not have been recreated in Vienna or Paris or Washington or anywhere else. Here was China at its most indestructible, irreplaceable, untranslatable, hopeful.

I thought about the latent anger underneath the stunned public amazement at any non-Oriental running around loose. The race memory built from centuries of victimization has lost none of its bitterness; it is the cornerstone of modern China's much-fanfared opening to the West. The message: come on. Now we're ready for you. Now we're strong enough to take what we want from you, and leave you the rest, that inferno of corruption you created and drove us through for centuries. You deserve it. Fat, soft, hairy, rich, bignoses. One of the first expressions we teach our children is waiguoren, alien. They shout it at you on sight, jeer and point and laugh, and as soon as they have the strength throw things at you. Of course, when they can understand, we teach them manners, to be polite to you. We anxiously teach them enough of your language so they can go to your powerful institutes and factories and schools and learn the trick of how you created or stole all that wealth. But we don't have to teach them what you never knew, that there is no such thing as personal freedom, your euphemism for criminal license. They are Chinese. They are inheriting millenia of family discipline you barbarians have never dreamed of, and they will now, at last, beyond deserving, cash in that eon of expectation, clad in the just instrument of socialism, the benevolent state, the People's Republic.

What must it be like, I wondered, to be a Cantonese in, say, Canton, Illinois? Working backward from being an American in China, I imagine a Chinese would first notice a kind of general stimulus deficit. Nobody pushes him or runs into him. You can hardly hear people when they talk. No crowds in the middle of the street, no bicycle jams, nobody hauling slops on shoulder sticks. Sidewalks, stores, businesses, all half-deserted. No wonder. Look at the prices! But what stunning treasurehouses of things--who could possibly need all that? How do you decide which one to buy? And where do these people live? That's a house? For three people? Impossible. It must be some kind of park. But there are miles of them, scattered through this forest, with all that--what is it? Grass? It must be terribly lonely to live in such grand isolation. And the people have to pay for those palaces themselves, out of jobs and careers they are left to themselves to find? Then what is the government for? Besides capitalist warmongering, it seems to do little else. No wonder Americans can and do say such shocking things about their leaders. So much wealth, no purpose. It's a great place to visit, but I wouldn't want to live here.

I guess by now you don't want to hear any more of my dreary horror stories about public transportation in China, so I won't try to take you back to Changsha with us. In fact, I'd advise you to stay right there in Guangzhou, with its monster banyans and temples, traffic jams and river jams, money hawkers and famous food, mad business, hills, hotels, markets, miseries, millions. It's one of the world's great places to be.

China High and Low

I suppose it's impossible for any but an inconceivable dullard to come to China without expecting some kind of cultural apocalypse. At the high end of the sophist scale will be a few who have taken to heart the Buddha's teaching that to expect is to illude, the central, catastrophic cause of suffering, but they are maybe even more dangerously at risk than the common blind romantic, who at least has the option of believing that he sees what he wants to see. I thought I could score pretty high on the reality meter when I came. Having studied the theory of Buddhism (what a typically Western way to go at a religion) and having fooled around superficially with its practice (which aims to annihilate theory), I had at least learned to sort of cheat the fear of disappointment, but not otherwise got much closer to direct, unconditional surrender to awareness, or enlightenment, or the ineffable Tao, or whatever. I was and am still I, and China was and for me still is China, not both one transparent continuum, no blessed revelation of the divine absolute. I still see through the glass, although, I believe, not so darkly.

But the view has changed. That would of course be impossible had I really had no desires or hopes or concepts or illusions or crazy notions or mortal flaws when I first got shoved off a train into a filthy, swarming, Chinese railway station. Nearly thirty years had passed since I had first laid mind on classical Chinese thinking at the freie Universität in Berlin and felt my heart and breathing steady and settle to the quietly fluid ladder of characters evoking peach blossoms and bamboo groves climbing sheer, holy pinnacles toward the temple. Little did I dream how my heart and breathing would labor, on the downslope of middle age, to haul the rest of my mortal carcass up those real crags to the souvenir shops at the peak.

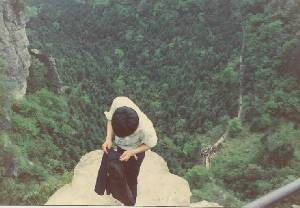

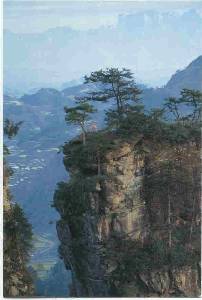

The highest point in Zhangjiajie ("borders of the Zhang clan") State Park in northwestern Hunan Province is 4048' 6" above sea level and laterally literally a stone's throw from its lowest at 1378'. I stood puffing in exultation on the peak and wondered how many unnecessary people had made the trip straight down, the shortest, fastest, stone's-throw way, there being not the slightest warning, forget guard rails, at the most gut-clenching, plain-space dropoffs.

Somehow the wisdom and antiquity of China have settled into an eternally vertical image, the most stunning and holiest mountains rising like stacked exclamation points, rice paper scroll paintings stretching from floor to ceiling, poems climbing their margins, the bamboo shooting up in calm levity, the squalid pig-ridden peasant looking up to the magistrate, the scholar, the emperor, the dragon beyond heaven. And up the sheer flanks of Zhangjiajie climb the stone steps, across mad little brooks, through Edenically vegetatious creases, around incredible switchbacks up hypervertical bald cliff faces into the sky full of crazy azaleas hanging out of gorgeously dizzy crevices.

Stone. A meter-wide, hand-laid, unfailing stair of stone, all the way up. On May Day,every step of it was swarmed with people, yelling, spitting, whistling, camera- and-lunch-strung, looking from far below or above very much like the clichéd colorful, eternal stream of ants. But the next day the spires and valleys swirled in and out of lightning fog and rain oceans, the steps turned to sparkling waterfalls, and we splashed up and down them without having to elbow our way. A couple of hours of increasingly steep climbing brought us to a high natural bridge, where the wind whipped storm clouds through a colossal short cut from one canyon into the next. After shivering and laughing in giddy astonishment and clambering anxiously over stones and mud paths, we descended through caverns measureless to man. And there the sacred river ran, much enthused from the towering curtains of rain sinuating between the cliffs, a stupendous aurora of spray falling with the leisure of eternity.

If there is blessedness in sheer nature, it was here. I stood, soaked, on an elephant-smooth rock, my aging thighs wobbly, the river at my feet now a merry tumult, my face turned up to the streaming sky, vast thunder-shaken lanes of cloud majestically parted by those incredible, conifer-mustached columns. I let down the door to the spirit.

In the simultaneous tangible world, Julia and a friend wrangled cameras. I uselessly elevated an umbrella. We were wet as fish. To climb back over the incredible pass we had just come through wasn't in us. We would follow the river up the valley to the hotel again, if we could get across to the stone path on the other bank. Julia, typically, assaulted a chain of rocks over and through which gushed rapids (the week before she had taken it into her head or whatever to drop her bike and jump into the great muddy Xiangjiang, clothes, shoes, ID cards and all, and duplicated Mao's famous river-crossing method, of which she had never heard until I told her afterwards). With visions of daughter and kit and passports flushing away into the China Sea, I countermanded, and we succeeded instead in teetering over slick logs laid across at an intended bridge site. I doubt the rocks would have been as perilous.

Well, we got back, I'm here to tell you, and wandered around, still soaked, in the little village that spoiled the valley like a trash moraine rinsed down from the noble heights towering over it. Noodle sellers, scorched cooking smoke, tourist junk, hornblasting buses streaked with vomit and mud, a hifi speaker bellowing out the window over the lively pool table in the gutter, a tent city, the town louts getting a start on their evening drunk. Piles of shit on the steps down to the stream where women washed clothes. Here and there in the lolling crowds another paleface or two. Snatches of Austrian, French, American. High above, the mountain forests darkened from green to black, the rock spires from limestone orange to moody grays. This was it. Here was China.

We stopped next day on the way back to Changsha at the famous Peach Blossom Source near Yiyang, a garden fabled in ancient calligraphy, and there they were again--the stone steps. Up and down the lush mountainside, past caves, pools, waterfalls, through groves of thigh-thick, cathedral-tall giant bamboo to a Mingish-looking temple complex, fronted with photos of touring dignitaries, dusty Buddhas inside. A big iron bell in one corner, in the other an immense drum, silently recumbent high on its timber stand. From what creature the hide covering it must have come I couldn't imagine; some mythical monster seemed appropriate. I reached up and tapped it gently. Thunder as though from mountain storms miles above and forever past muttered deeply among the vast, lacquered roof beams. Julia, had she been there, of course would have slammed it with her fist or a bottle or something handy, and turned all the thunder loose. But she was off romping through a cave somewhere, and I was timidly, respectfully alone. The gut-stirring bass drone took as long to die away as it has taken you to read this description.

When I got back to the entrance gate, Julia and Gabie Jagau, the German teacher from Hannover, stood semicircled by a crowd of Mao-jacketed men, staring, poking each other, giggling. The remarks had gotten to the "hey, not bad looking" stage. Gabie aimed her Minox at them. They parted and rolled back like the Red Sea, ducking and joking. A local bus stopped. Hopeful passengers, yelling and waving, erupted from the restaurant across the street. Last came a young woman, brandishing chopsticks and spewing rice, who, shouldering aside attempts to shut the bus door on her, reached in and grabbed a man by the jacket tail, and after a noisy tussle hauled him back out. The bus coughed away.

Behind the iron gate, high on the hillside amid soaring bamboo trunks, the temples waited by the stone pathways. Our party collected, piled into our bus, and roared on.

What Dragons are for

Just as sacred mountains or grottoes are capped with temples of one kind or another to keep their mysterious divinity from evaporating, so too do we knit legends around the ancient festivals of the planets and seasons to dress their rude primal meanings in a style more suited to civilized enlightenment. Gods, kings, and sacrifice victims have always been specially prone to rise from the dead as spring approaches, in time to bless, if not help with, the planting.

I don't know of any parahuman champion in Chinese of the divinely regenerative germ plasm. His place is taken by the most powerful symbol of life itself: the dragon. That marvelous being's patron day is made to fall on the double fifth in the lunar calendar, fifth day of the fifth month, a number to drive astrologers and occultists to spasms of exegesis and the rest of China to the river banks for the Dragon Boat Festival.

Ritual always calls for sacrifice, of course. To the everlasting credit of the Chinese, they had already progressed in their spring ceremony to the sophistication of casting special rice cakes upon the waters to feed the soul of a drowned poet while many another so-called civilization was still wreaking horrible self-mutilations or flinging its children into whatever chthonian pits thought holy. China must be the last realm on earth where poets still have some claim to divinity, even though required to drown first. As for nourishment, nowhere have live poets ever been supposed to need it. The protagonist of the present legend, one Qu Yuan, is said to have incurred royal disfavor and thrown himself into the river in despair on the double-fifth in what we now reckon as 278 B.C. And in that massive, incessant, life-giving stream he found the sustenance and veneration before denied him. It is worth noting that the few handsful of rice cakes rationed out to him once a year amount not even to a ripple among the kilotons of them swallowed by the living, who also dredge up the rice-fattened fish and swallow them too. Economically and sanitarily so much sounder a religion than dropping maidens in the well.

The dragon, remarkably, doesn`t need to be propitiated. He is power and wizardry. He does not lurk hungering for sacrifices. He races. In his avatar as boat, with irrepressibly fanciful savage grin, scales, flashlight eyes, contorted crepepaper tails and flourishes (I saw one with nodding red bugball sproingy antennae, a most lovable monstrosity), he carries teams of maddened paddlers on his back, lashed by the clang of much gongbashing toward the screaming finish line. Or, between heats, cargoing a raucously patriotic brass and percussion uproar, camera-ridden media types, and dignitaries, advertising a local factory on his flanks, he cruises majestically past the crammed review stands on the factory roof, spewing squealing skyrockets and rhythmically farting outboard motor smog.

As racially irrefutable dignitaries, Julia and I had front-row benches down in the mud, where the action is, to watch the first-day matches (like all real festivals, this one overpowers everything else for weeks before) at Yueyang, an otherwise not overpowerfully significant settlement amid the vast floodplain lakes where the Xiang and Chang conflue (check your almanac under Yangtze for statistics). The drowned poet legend claims indigenosity to the lower Xiang here in northern Hunan Province. Racing teams come to compete from cities of the province far up- and downstream, exactly how far I confess I can't say, having failed to find a program for sale among the souvenir and sodapop clutter, and not ready to claim I understood anything useful of what the squawkboxes bellowed inbetween skypiercing Puccini arias howled in Chinese, Beijing-opera style.

The rowing teams mustered in bright uniforms under handpaddles marked with their home city (I could read a few of them), rather than a work unit or institution, as would have been more typical of the universal socialist brigade structure. The dragon is not powered by the proletariat. His vitality wells up from somewhere as deep as instinct, however it may be paraded. The teams of 34 oarsmen (one had 36; maybe their dragon had a barnacle handicap?) of every size, shape, and age, plainly amateurs, lined up squadwise at attention under command of their likewise amateur coxwain, all gymsuited and barefoot in the mud. They slithered through a semblance of military-style countoff and marching drill down to board their dragon-dressed racing sampans. The whole rig once afloat with everybody thrashing at the water more or less in synchrony with the stroking gong looked like some bizarre aquatic caterpillar frantic to get somewhere fast. The heats went on all morning, three dragons to a match. The band blurted the march always played at competitions, over and over. The crowd roared in triumph or dismay or maybe just for the hell of it as each race finished and again when the times were blasted out over the blasting system. The victorious or beaten teams returned to wade up the now thoroughly quagmired banks to retrieve piled clothes and shoes and soak up a sicklysweet orange soda. The dragon re-emerged in his brassband advertising regalia to cruise by the thronged banks, majestically, unhurriedly, eternally. It was time for us to go.

Go to Part Four